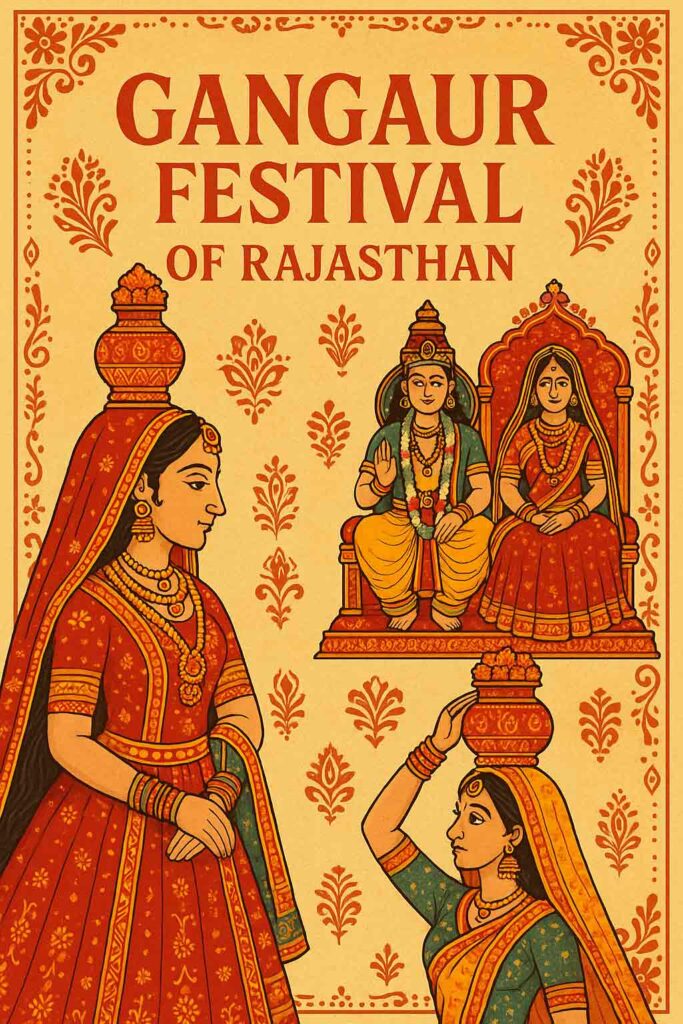

Gangaur

Gangaur Festival (February–March) A Celebration of Love, Devotion, and Spring Gangaur is one of the most vibrant and culturally rich festivals celebrated primarily in the Indian state of Rajasthan, though its influence and spirit extend to parts of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal. The festival is dedicated to Goddess Gauri, an incarnation of Goddess Parvati, who symbolizes marital bliss, love, and fertility. The name “Gangaur” is derived from two words—“Gana,” another name for Lord Shiva, and “Gaur,” referring to Goddess Gauri or Parvati. Thus, Gangaur is essentially a celebration of the divine union of Shiva and Parvati and represents the ideals of love, fidelity, and devotion between husband and wife. Celebrated with great enthusiasm and grandeur, Gangaur begins the day after Holi and continues for eighteen days, culminating with elaborate processions, rituals, and festivities. It marks the arrival of spring and harvest time, a period of renewal and prosperity. For women, Gangaur is a festival of immense personal significance. Married women worship Goddess Gauri for the long life, health, and happiness of their husbands, while unmarried girls pray to the goddess for a suitable life partner. The festival, therefore, intertwines social, spiritual, and emotional dimensions, reflecting the deep-rooted cultural traditions of Rajasthan. The rituals of Gangaur are a beautiful blend of devotion and artistry. Women, adorned in their finest traditional attire and jewelry, observe fasts, sing folk songs, and decorate their hands with intricate mehndi (henna) designs. Clay idols of Gauri and Isar (Shiva) are crafted and decorated with colorful attire and ornaments. These idols are worshipped daily, and offerings of wheat, barley, and flowers are made. In rural areas, unmarried girls carry small earthen pots called “ghudlias,” adorned with lamps, through the streets while singing traditional songs, symbolizing light, prosperity, and hope. As the festival progresses, the rituals intensify, leading to the final two days that are marked by spectacular celebrations. On the penultimate day, the idols of Isar and Gauri are placed on decorated wooden platforms or on the heads of women, and grand processions move through the towns and villages. Accompanied by traditional music, dancing, and folk performances, these processions are a feast for the eyes and a true representation of Rajasthan’s colorful culture. The festival reaches its climax when the idols are immersed in water bodies, symbolizing the return of Gauri to her husband’s abode. Jaipur, the capital city of Rajasthan, is particularly famous for its grand Gangaur celebrations. The royal family often participates, and beautifully decorated elephants, camels, and horses lead the traditional procession from the City Palace through the streets of the Pink City. Locals and tourists alike gather in large numbers to witness the spectacle, making it one of the most photographed and cherished events in Rajasthan’s cultural calendar. Udaipur, Jodhpur, and Bikaner also host equally magnificent celebrations, each adding its regional flavor to the festival. Beyond the rituals and festivities, Gangaur carries profound symbolic meanings. It represents the essence of womanhood, devotion, and the sacred bond of marriage. The festival also acknowledges the cycles of nature, the importance of fertility, and the harmony between human life and the environment. For young girls, it serves as an initiation into traditional customs and values, while for the older generation, it is an opportunity to pass on cultural heritage and familial wisdom. In today’s times, while lifestyles have modernized, Gangaur continues to hold its charm and relevance. It stands as a reminder of India’s cultural diversity, the strength of traditions, and the enduring power of faith and love. Whether celebrated in the courtyards of small villages or on the grand streets of Rajasthan’s royal cities, Gangaur unites people through devotion, beauty, and the eternal rhythm of life and nature.

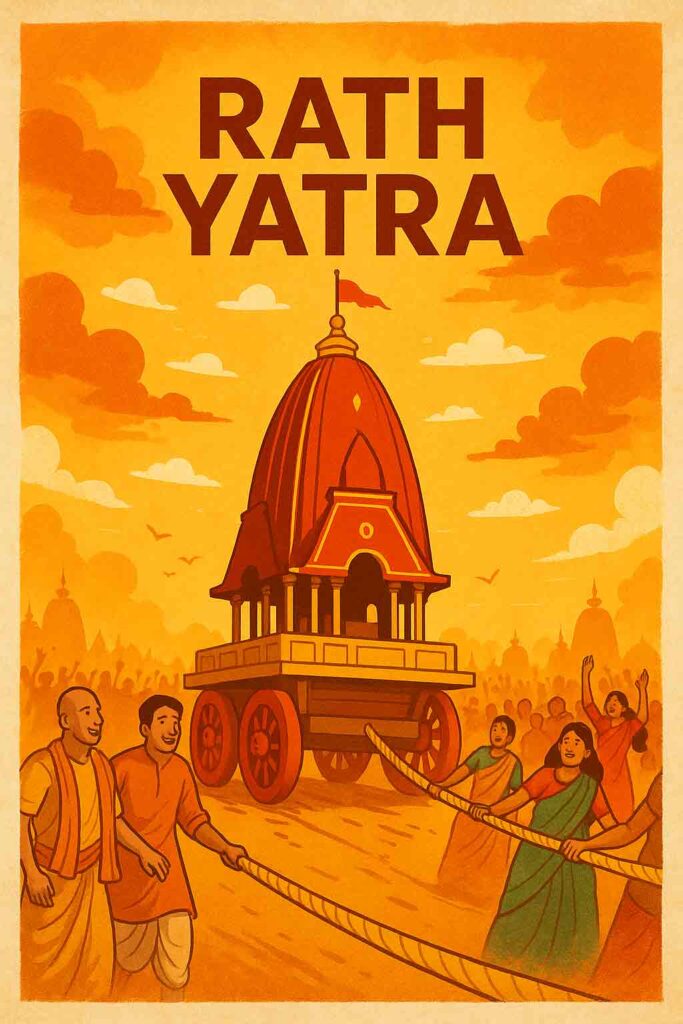

Rath Yathra

Rath Yatra (June–July) Chariot festival of Lord Jagannath Rath Yatra, also known as the Chariot Festival, is one of the grandest and most celebrated Hindu festivals in India, dedicated to Lord Jagannath (a form of Lord Vishnu), his brother Balabhadra, and sister Subhadra. The festival, held annually in the sacred city of Puri in Odisha, attracts millions of devotees from across India and the world. The word “Rath Yatra” literally translates to “Chariot Journey”, symbolizing the divine journey of the deities from their main temple to another temple, signifying the Lord’s visit to his devotees. This festival, marked by devotion, color, music, and enthusiasm, reflects the deep spiritual bond between the divine and humanity and celebrates inclusivity, unity, and faith. The central event of the Rath Yatra is the grand procession of the three majestic chariots carrying the idols of Lord Jagannath, Lord Balabhadra, and Devi Subhadra from the Jagannath Temple to the Gundicha Temple, about three kilometers away. Each deity has a beautifully crafted wooden chariot made anew every year using sacred neem wood, following centuries-old traditions. The chariots are massive structures, towering up to 45 feet high, adorned with bright colors, intricate designs, and canopies of red, yellow, green, and blue. The chariot of Lord Jagannath, called Nandighosa, has 16 wheels; Balabhadra’s chariot, Taladhwaja, has 14 wheels; and Subhadra’s chariot, Darpadalana, has 12 wheels. Thousands of devotees, regardless of caste, creed, or social status, gather to pull the ropes of these chariots, as it is believed that pulling the chariot grants immense spiritual merit and the blessings of Lord Jagannath himself. The Rath Yatra holds immense religious significance. It is believed that Lord Jagannath, along with his siblings, travels to the Gundicha Temple, which is considered to be the home of their aunt. The journey symbolizes the Lord’s desire to come out of the temple to bless all devotees, including those who cannot enter the sanctum sanctorum due to traditional restrictions. This act of accessibility makes the festival a symbol of equality and inclusiveness in Hindu spirituality. After spending nine days at the Gundicha Temple, the deities make their return journey, known as the Bahuda Yatra. The return procession is equally festive, filled with chants, drumbeats, dancing, and joyous devotion. The festival’s origins are deeply rooted in mythology and tradition. It is said that the practice of Rath Yatra dates back thousands of years and is mentioned in ancient Puranas like the Skanda Purana, Padma Purana, and Brahma Purana. According to one popular legend, the divine siblings longed to visit their birthplace, Gundicha Temple, which represents their maternal home, and thus began the annual chariot journey. Another belief associates the festival with Lord Krishna’s return to Vrindavan, symbolizing his eternal bond with his devotees. The rituals associated with Rath Yatra start much earlier with Snana Purnima (the bathing festival), followed by a fortnight-long period known as Anasara, during which the deities are believed to fall ill and remain in seclusion before appearing again in public during the Yatra. Apart from Puri, Rath Yatras are celebrated in many parts of India and abroad, especially in places with large Jagannath temples such as Ahmedabad, Kolkata, and Delhi. The International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) has popularized the festival globally, and today, Rath Yatras are held in major cities like London, New York, Sydney, and Singapore, drawing devotees from all backgrounds. The atmosphere during the festival is electrifying—streets are filled with devotees singing devotional hymns, chanting “Jai Jagannath!”, and dancing in divine ecstasy. Vendors sell traditional sweets like khaja and poda pitha, while temples and homes are decorated with flowers and lights, enhancing the festive spirit. Beyond its religious fervor, the Rath Yatra embodies profound philosophical meaning. It represents the journey of the soul toward liberation (moksha), guided by divine will and devotion. The pulling of the chariot symbolizes the effort one must make to move closer to the divine by overcoming worldly attachments. The festival teaches humility, service, and unity, reminding devotees that the divine resides not only in temples but within every heart that seeks with love and sincerity. Rath Yatra thus transcends mere ritual—it is a celebration of faith, devotion, and the eternal bond between God and humanity.

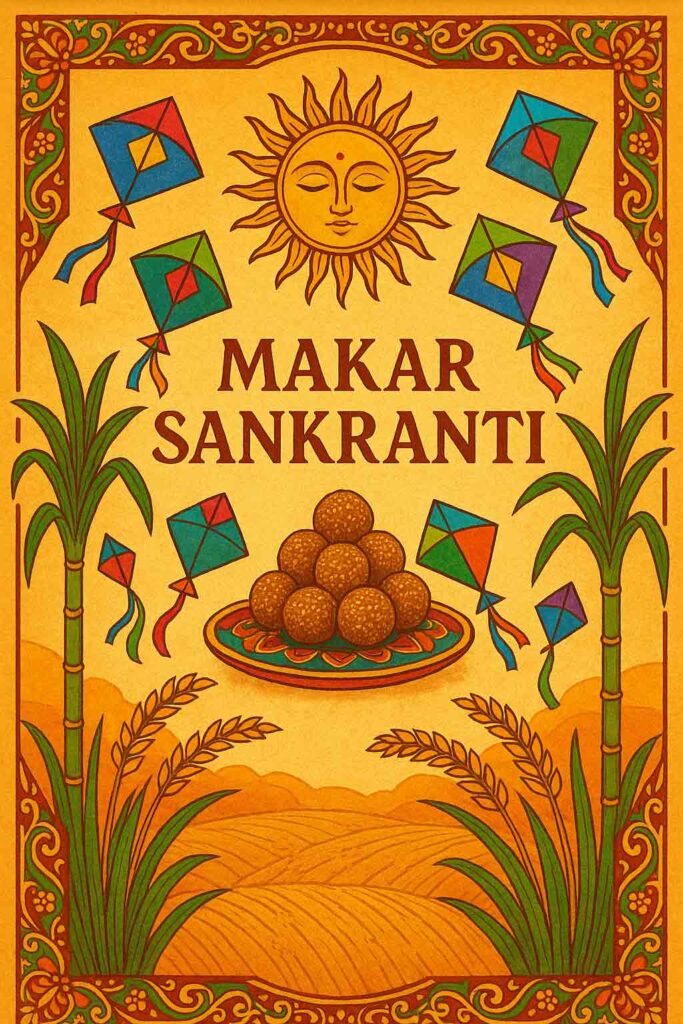

Makar Sankranti

Makar Sankranti (January 14) The Festival of Sun, Harvest, and New Beginnings Makar Sankranti, one of India’s most ancient and widely celebrated festivals, marks the transition of the Sun into the zodiac sign of Makara (Capricorn) and signifies the end of the winter solstice. This celestial event, usually occurring on January 14th each year, heralds longer and warmer days, symbolizing hope, prosperity, and the renewal of life. It is among the few Indian festivals that follow the solar calendar, which is why its date remains constant, unlike other festivals that shift according to the lunar calendar. Across the country, Makar Sankranti is celebrated with different names, customs, and traditions, but its underlying spirit—gratitude for nature’s bounty and the celebration of the harvest—remains universal. The festival holds deep agricultural significance. It marks the time when farmers rejoice after months of hard work during the harvest season. The granaries are full, and the land, having yielded its produce, becomes a symbol of abundance and sustenance. People express their gratitude to the Sun God (Surya Dev), whose warmth and light are essential for growth and life. In rural India, Makar Sankranti is closely tied to nature’s rhythms; it is a day when farmers rest, celebrate, and pray for good harvests in the coming year. Offerings of the first crops—especially newly harvested grains, sugarcane, sesame (til), and jaggery (gur)—are made in rituals, highlighting the deep bond between human life and the natural world. Each region in India celebrates Makar Sankranti with its own distinctive flavor and traditions. In North India, particularly in Punjab and Haryana, it coincides with Lohri, a festival of bonfires, dance, and song. People gather around the fire, throwing puffed rice, popcorn, and sesame into the flames as offerings, symbolizing the burning away of the old and the welcoming of new beginnings. In Gujarat and Rajasthan, the sky becomes a canvas of vibrant colors as people engage in kite flying, a hallmark of the festival. The kites, soaring high against the blue sky, represent freedom, joy, and human aspirations reaching toward the heavens. The International Kite Festival in Ahmedabad is a spectacular sight, attracting participants from across the globe. In Maharashtra, Makar Sankranti is marked by the exchange of sweets made of sesame seeds and jaggery, accompanied by the saying, “Tilgul ghya, goad goad bola,” which means “Accept this sweet and speak sweetly.” This gesture symbolizes the need to forget past grievances and embrace kindness and harmony in relationships. In Tamil Nadu, the festival is celebrated as Pongal, a four-day thanksgiving festival dedicated to the Sun God, cattle, and the Earth. Homes are decorated with kolams (rangoli designs), and rice is cooked in earthen pots until it overflows—a ritual that signifies abundance and prosperity. In Assam, it takes the form of Bhogali Bihu, characterized by feasting, traditional games, and community bonfires, while in Bengal, devotees take holy dips in the Ganges and offer prayers to the rising sun during Gangasagar Mela. The symbolism of Makar Sankranti extends beyond harvest and celestial transitions; it embodies themes of renewal, light, and self-reflection. As the sun begins its northward journey (Uttarayan), the festival encourages people to turn toward positivity, learning, and growth. The movement from darkness to light mirrors the inner spiritual journey—rising above ignorance and embracing knowledge and wisdom. Traditionally, taking a holy dip in rivers like the Ganga, Yamuna, or Godavari is believed to cleanse sins and purify the soul. The act of charity (daan), especially of food, clothes, and money to the poor, is also an essential part of the celebration, signifying compassion and social responsibility. Makar Sankranti thus serves as a reminder of the timeless connection between humans and the cosmos, between effort and reward, and between gratitude and generosity. It brings families and communities together in joy, reflection, and thanksgiving. The sight of colorful kites dancing in the sky, the warmth of sesame sweets, the rhythm of folk songs, and the laughter that fills the air all echo a single message—the end of darkness and the dawn of light. Beyond rituals and traditions, Makar Sankranti inspires us to rise higher, stay grounded in gratitude, and celebrate life’s simple yet profound cycles with a heart full of hope and positivity.

Ugadi

Ugadi (March–April) The Joyous Beginning of a New Year Ugadi, also known as Yugadi, is one of the most important and joyous festivals celebrated in the southern states of India, particularly Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, and parts of Maharashtra. The word “Ugadi” is derived from two Sanskrit words—Yuga meaning “age” and Adi meaning “beginning.” Thus, Ugadi signifies the beginning of a new age or era. It marks the New Year as per the lunisolar Hindu calendar, usually falling in March or April. The festival heralds the arrival of spring and the onset of the new harvest season, bringing with it a sense of renewal, hope, and prosperity. It is a time for new beginnings, reflection, and gratitude, when people welcome the future with positivity and celebrate the abundance of life. The significance of Ugadi goes beyond being just a New Year celebration; it is deeply rooted in cosmic, agricultural, and spiritual symbolism. According to Hindu mythology, it is believed that Lord Brahma, the creator of the universe, began his work of creation on the day of Ugadi. Therefore, it is considered an auspicious time to start new ventures, make important decisions, and set goals for the coming year. Ugadi also coincides with the time when nature undergoes renewal—the trees sprout fresh leaves, flowers bloom, and the fields begin to flourish. This natural rejuvenation mirrors the inner transformation that people seek during the festival, as they let go of the past and embrace a new cycle of life with optimism and faith. The celebrations of Ugadi begin early in the morning, as devotees rise before sunrise and take a ritualistic oil bath, considered a symbolic cleansing of both body and mind. Homes are cleaned thoroughly and decorated with muggu (rangoli) designs at the entrance, and fresh mango leaves are tied to doorways as a symbol of auspiciousness and prosperity. People wear new clothes and gather with family members to perform traditional prayers. One of the central rituals of the day is the preparation and consumption of the famous Ugadi Pachadi, a special dish that embodies the essence of life itself. Ugadi Pachadi is made from six ingredients—neem flowers (bitter), jaggery (sweet), tamarind (sour), raw mango (tangy), salt (salty), and green chili (spicy). Each flavor represents different emotions and experiences of life: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust. The mixture serves as a philosophical reminder that life is a blend of varied experiences, and one must accept them all with equanimity. It teaches an important lesson of balance, resilience, and acceptance—a reflection of the true spirit of the festival. Apart from the rituals at home, temples are beautifully decorated, and special prayers are conducted to seek divine blessings for health, wealth, and peace in the year ahead. Astrologers prepare the Panchanga Shravanam—the traditional reading of the Hindu almanac—that forecasts events and fortunes for the coming year. This reading is an integral part of Ugadi celebrations, guiding people on what to expect and how to prepare spiritually and mentally for the future. The festive atmosphere extends beyond homes into communities and towns. Cultural programs, music, dance, and traditional performances mark the celebrations. People exchange greetings, gifts, and sweets with neighbors and relatives, spreading joy and unity. For farmers, Ugadi holds special importance as it signals the beginning of the agricultural season. They offer prayers for good rains and bountiful harvests, thanking Mother Earth for her generosity. Ugadi is not merely a festival of rituals—it is a celebration of renewal and inner awakening. It inspires individuals to reflect upon their actions, make positive resolutions, and strengthen their relationships. It is a day to forgive, forget, and move forward with hope. The festival reminds everyone that like the cycles of nature, life too is ever-changing and full of new possibilities. As the sun rises on Ugadi, lighting up the sky with brilliance, people are reminded that every dawn is an opportunity to begin again—to create, to grow, and to live meaningfully. Ugadi thus stands as a beautiful symbol of life’s eternal rhythm—a time to rejoice in the present, honor the past, and embrace the future with renewed spirit and gratitude.

Onam

Onam (August–September) The Festival of Harvest, Harmony, and Heritage Onam is one of the most vibrant and cherished festivals of Kerala, celebrated with immense enthusiasm, cultural splendour, and unity among people of all communities. It marks the annual homecoming of the mythical King Mahabali, whose reign is remembered as a golden age of prosperity, equality, and happiness. The festival, which usually falls in the Malayalam month of Chingam (August–September), is Kerala’s official state festival and symbolizes the spirit of togetherness, harmony, and gratitude for nature’s bounty. Onam is not just a festival — it is a cultural experience that reflects the very essence of Kerala’s traditions, arts, and community life. The legend behind Onam is rooted in Hindu mythology. King Mahabali, an Asura (demon) king, was known for his generosity, justice, and devotion to his people. His reign brought prosperity and peace to the land, and everyone lived happily without discrimination or sorrow. However, the gods grew concerned that Mahabali’s fame and power were surpassing theirs. To humble him and restore cosmic balance, Lord Vishnu took his fifth avatar as Vamana, a dwarf Brahmin. When Mahabali offered him a gift, Vamana asked for three paces of land. With two steps, he covered the earth and the heavens, leaving no space for the third. The noble Mahabali then offered his head for the final step, and Vishnu sent him to the netherworld (Patala). Impressed by his devotion and humility, Lord Vishnu granted Mahabali permission to visit his people once every year. Onam commemorates this annual visit, celebrating the time when the beloved king returns to see his prosperous and joyful kingdom. The ten-day festival of Onam begins with Atham and concludes with Thiruvonam, the most auspicious day. The celebrations are marked by elaborate rituals, traditional games, cultural performances, feasts, and decorations. One of the most iconic symbols of Onam is the Pookalam, a beautiful floral carpet designed in intricate patterns at the entrances of homes. Each day, fresh flowers are added, creating a colourful and fragrant welcome for King Mahabali. The Pookalam symbolizes harmony, creativity, and the community’s collective joy. Another highlight of Onam is the grand Onam Sadya, a traditional vegetarian feast served on a banana leaf. It includes a variety of delicious dishes — from avial, sambar, olan, and thoran to crispy pappadam and sweet payasam. The Sadya represents abundance and gratitude for nature’s harvest and is enjoyed with family and friends, reinforcing the values of sharing and togetherness. The festival also showcases Kerala’s rich cultural heritage through music, dance, and sports. Traditional art forms such as Kathakali, Thiruvathirakali, Pulikali (the tiger dance), and Vallamkali (the famous snake boat race) are performed across the state. Vallamkali, in particular, captures the spirit of Onam — hundreds of oarsmen row their long, decorated boats in perfect rhythm to the beat of drums, cheered on by thousands of spectators. These events are not merely entertainment; they are expressions of Kerala’s communal harmony, teamwork, and cultural pride. Onam also has a deep philosophical meaning that transcends religion. It celebrates the virtues of humility, generosity, and righteousness as embodied by King Mahabali. The festival reminds people that true prosperity lies not in wealth but in kindness, unity, and mutual respect. It is a time when people forget social differences and come together as one community, decorating their homes, exchanging gifts, and rejoicing in the spirit of equality. In modern times, Onam has evolved into a global celebration of Malayali culture. People of Kerala, wherever they live — across India or abroad — observe the festival with the same devotion and joy. Onam bridges generations and geographies, keeping alive the values of harmony and gratitude that define Kerala’s identity. Ultimately, Onam is a celebration of life — of good harvests, moral virtue, and cultural pride. It reminds everyone of a utopian time under a noble ruler when happiness, fairness, and prosperity prevailed. As the lamps glow, the Pookalams bloom, and the aroma of Onam Sadya fills the air, every heart in Kerala and beyond welcomes King Mahabali with love and says, “Maveli naadu vaneedum kaalam, manusharellarum onnu pole” — “When Mahabali ruled the land, all people lived as equals.”

Raksha Bandhan

Raksha Bandhan (July–August) The Sacred Bond of Love and Protection Raksha Bandhan, also known as Rakhi, is one of the most cherished festivals in India, symbolizing the pure and affectionate bond between brothers and sisters. The term “Raksha Bandhan” literally means “the bond of protection,” derived from the Sanskrit words Raksha (protection) and Bandhan (bond). Celebrated on the full moon day (Purnima) of the Hindu month of Shravan (July–August), this festival holds immense emotional and cultural significance. On this day, sisters tie a sacred thread called rakhi around their brothers’ wrists, praying for their health, happiness, and long life. In return, brothers promise to protect their sisters from harm and stand by them in times of need. This simple yet profound ritual celebrates not only familial love but also the timeless values of trust, care, and mutual respect. The origins of Raksha Bandhan can be traced back to ancient Indian mythology and history. Several legends narrate how the festival came into being. One of the most popular stories is that of Lord Krishna and Draupadi. When Krishna injured his finger, Draupadi tore a piece of her saree and tied it around his wound to stop the bleeding. Deeply touched by her gesture, Krishna vowed to protect her always, a promise he fulfilled during the infamous disrobing scene in the Mahabharata. Another story tells of Queen Karnavati of Mewar, who sent a rakhi to Emperor Humayun, seeking his protection when her kingdom was threatened by Bahadur Shah. Honoring the bond, Humayun immediately came to her aid, showcasing that Raksha Bandhan transcends religion and caste, representing universal brotherhood and compassion. The festival also finds mention in various Puranas and historical texts. According to another legend, when Lord Indra, the king of the gods, was losing a battle against demons, his wife Indrani tied a sacred thread around his wrist, empowering him with divine strength to emerge victorious. Over time, Raksha Bandhan evolved into a social and family festival, celebrating the affectionate ties between siblings and loved ones. The celebration of Raksha Bandhan varies across regions but carries the same essence of love and protection. Preparations begin days in advance, with markets filled with colorful rakhis, sweets, and gifts. On the day of the festival, families gather for rituals. Sisters perform an aarti of their brothers, apply a tilak (vermilion mark) on their forehead, and tie the rakhi while chanting mantras that invoke divine blessings. The brother then offers gifts or money as a token of love and gratitude. Traditional sweets like ladoos, barfis, and kaju katli are shared, filling homes with joy and warmth. In modern times, the festival has also embraced digital forms—sisters send e-rakhis or courier rakhis to brothers living far away, ensuring that physical distance does not weaken emotional bonds. Beyond the rituals, Raksha Bandhan carries a deeper social and cultural message. It reinforces the importance of familial relationships, love, and responsibility. In contemporary society, the festival’s meaning has broadened—people tie rakhis to friends, neighbors, and even soldiers as a gesture of solidarity and gratitude. Many women tie rakhis to the soldiers of the Indian Armed Forces, acknowledging their role as protectors of the nation. This extension of the festival reflects its universal message of peace, unity, and brotherhood. Raksha Bandhan is also a reminder of India’s rich cultural heritage that celebrates human emotions and relationships. It promotes the idea of coexistence, equality, and care for one another. For children, it is a joyful day filled with laughter, sweets, and excitement, while for elders, it rekindles family ties and cherished memories. The sacred thread of rakhi thus becomes more than just a decorative band—it becomes a symbol of faith, commitment, and eternal love. In essence, Raksha Bandhan stands as a celebration of human connection in its purest form. It teaches that protection and love are not bound by gender, religion, or distance but are universal values that unite all. As sisters tie the rakhi and brothers pledge to protect, the festival renews the spirit of care and mutual respect that strengthens families and communities. Every Raksha Bandhan reminds us that while threads may fade with time, the bond of love and protection they signify remains eternal, woven deep within the heart of every sibling relationship.

Maha Shivratri

Maha Shivratri (February–March) The Night of Lord Shiva’s Cosmic Dance Maha Shivratri, one of the most sacred festivals in Hinduism, is a grand celebration dedicated to Lord Shiva, the destroyer and transformer in the holy trinity of Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesh (Shiva). The term “Maha Shivratri” means “The Great Night of Shiva,” and it falls on the 14th night of the dark fortnight in the Hindu month of Phalguna or Maagha (February–March). On this auspicious night, devotees stay awake in reverence and devotion to Lord Shiva, observing fasts, performing rituals, and meditating deeply to attain spiritual growth and divine blessings. Maha Shivratri symbolizes the convergence of Shiva and Shakti—the masculine and feminine cosmic energies that sustain the universe. It is believed to be the night when Lord Shiva performed the Tandava, the cosmic dance of creation, preservation, and destruction, marking the eternal rhythm of life and the universe. The festival holds deep philosophical, spiritual, and mythological significance. According to one legend, Maha Shivratri marks the day when Lord Shiva married Goddess Parvati. Their divine union represents the balance between strength and compassion, austerity and grace. Another belief states that it was on this night that Lord Shiva consumed the deadly poison Halahala that emerged during the churning of the ocean (Samudra Manthan) to save the universe from destruction. The poison turned his throat blue, earning him the name Neelkanth—the blue-throated one. For ascetics and yogis, Maha Shivratri is not merely a festival but a spiritual opportunity to overcome ignorance, conquer desires, and experience inner peace through meditation and devotion to Lord Shiva, the Mahadeva—the great god who resides in Mount Kailash in deep meditation. Across India and in many parts of the world, Maha Shivratri is celebrated with immense enthusiasm and devotion. Temples dedicated to Lord Shiva are beautifully decorated, and devotees throng from early morning to offer their prayers. The day begins with ritualistic bathing of Shiva Lingams—symbols of the formless divine energy—with milk, honey, water, ghee, sugar, and curd, known collectively as the Panchamrit Abhishek. Offerings of bael (bilva) leaves, dhatura flowers, fruits, and incense are made to please the Lord. Chanting of the Mahamrityunjaya Mantra and “Om Namah Shivaya” echoes through temples and homes, filling the atmosphere with spiritual vibrations. Many devotees observe strict fasts—some abstaining from food and water entirely—while others partake only in fruits and milk. The night-long vigil, known as Jagaran, is marked by devotional songs, bhajans, and recitations of Shiva scriptures like the Shiva Purana. The four prahars (quarters) of the night each carry specific rituals, representing different stages of human consciousness leading to ultimate awakening. Maha Shivratri also carries a profound yogic and scientific significance. According to yogic traditions, on this night, the natural energy of the planet rises to its peak. It is said that keeping the spine erect during meditation or vigil allows this energy to flow upward, promoting inner balance and spiritual awakening. This is why devotees stay awake all night, chanting and meditating, aligning their energies with the cosmic vibrations of Shiva. The night symbolizes the triumph of light over darkness and ignorance, guiding devotees toward self-realization and unity with the divine. Beyond its religious dimension, Maha Shivratri is a festival that unites people across communities. It teaches detachment, humility, and faith in divine order. It reminds humanity that life is transient and that true liberation lies in surrendering one’s ego to the higher self. As dawn breaks after the night of fasting and devotion, devotees feel renewed—a sense of calm, purity, and divine connection fills their hearts. The fragrance of incense, the resonant sound of conch shells, and the rhythmic chants of “Har Har Mahadev” echo through temples and homes, symbolizing the presence of Shiva in every particle of creation. Maha Shivratri thus stands as a timeless reminder of Lord Shiva’s cosmic dance—an eternal rhythm that sustains the cycle of life, death, and rebirth—and inspires devotees to seek truth, discipline, and ultimate freedom.

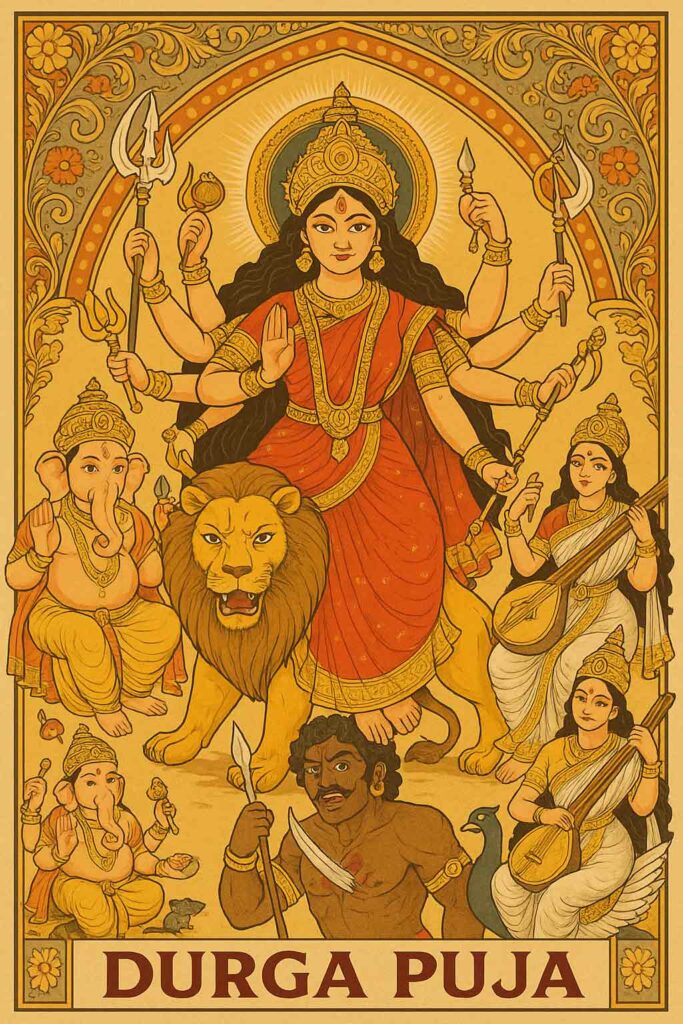

Durga Puja

Durga Puja (September–October) Honors Goddess Durga’s victory over Mahishasura. Durga Puja, one of the grandest and most cherished festivals in India, especially in West Bengal, is a magnificent celebration of the goddess Durga’s victory over the demon Mahishasura. It symbolizes the triumph of good over evil and the divine feminine power that protects and nurtures the world. Celebrated with unmatched fervour, artistic splendour, and spiritual devotion, Durga Puja is not merely a religious festival — it is a cultural phenomenon that unites communities, inspires creativity, and fills the atmosphere with joy, devotion, and festivity. According to Hindu mythology, Mahishasura, a powerful demon, gained immense strength through a boon that made him invincible against men and gods. Drunk with power, he unleashed terror across the heavens and the earth. To restore balance, the gods combined their energies to create Goddess Durga, a divine embodiment of Shakti — the supreme feminine power. Armed with weapons given by different deities and riding a majestic lion, Durga fought Mahishasura for nine days and nights, finally defeating him on the tenth day, celebrated as Vijayadashami or Dussehra. This epic battle represents the victory of truth, righteousness, and justice over tyranny and evil. Durga Puja is observed during the lunar month of Ashwin (September–October) and coincides with the last five days of Navratri. The celebrations begin with Mahalaya, which marks the invocation of the goddess. On this day, devotees wake up early to listen to the recitation of “Chandi Path” — verses from the Devi Mahatmyam — that narrate the story of Durga’s creation and her victory. The air fills with devotion as traditional songs, such as “Mahishasura Mardini,” echo across homes and temples, heralding the arrival of the goddess. The heart of Durga Puja lies in the magnificent pandals — temporary structures erected to house elaborately crafted idols of Goddess Durga and her children — Lakshmi, Saraswati, Kartikeya, and Ganesha. Each idol portrays Durga in her majestic form, slaying Mahishasura, symbolizing the triumph of divine energy. Artists and craftsmen spend months creating these idols and pandals, often turning them into breathtaking works of art that reflect themes from mythology, history, or even contemporary social issues. The creativity and artistry showcased during Durga Puja have made it one of the most spectacular cultural events in the world. For five days — Shashthi, Saptami, Ashtami, Navami, and Dashami — the cities and towns of Bengal come alive with lights, decorations, and festive music. People, dressed in their finest attire, visit pandals to offer prayers, socialize, and enjoy cultural programs. Traditional rituals such as Pushpanjali (offering flowers), Sandhi Puja (performed at the junction of Ashtami and Navami), and Dhuno Porano (offering incense to the goddess) are performed with devotion. One of the most powerful moments of the festival is the Dhak — the rhythmic drumming that fills the air and ignites the spirit of celebration. Food is another vital aspect of Durga Puja. Festive delicacies such as khichuri, luchi, cholar dal, beguni, sandesh, and rosogolla are shared among family and friends. Bhog — the sacred offering to the goddess — is distributed to devotees, symbolizing divine blessings. The festival is not just about worship but also about togetherness, joy, and cultural pride. On the final day, Vijayadashami, devotees bid farewell to the goddess with the ritual of Visarjan — the immersion of the idol in a river or sea. Women perform Sindoor Khela, smearing vermilion on each other in a joyous celebration of womanhood and prosperity. Though the immersion marks the physical departure of the goddess, it signifies the spiritual message that her divine energy remains within every devotee. Durga Puja transcends religious boundaries — it is a celebration of art, community, and the strength of good over evil. It reminds people of the power of righteousness, courage, and unity. In every beat of the dhak, in every lamp that glows, and in every smile that shines during the Puja, the spirit of Goddess Durga lives on — fierce, compassionate, and eternal — reminding humanity that light will always conquer darkness.

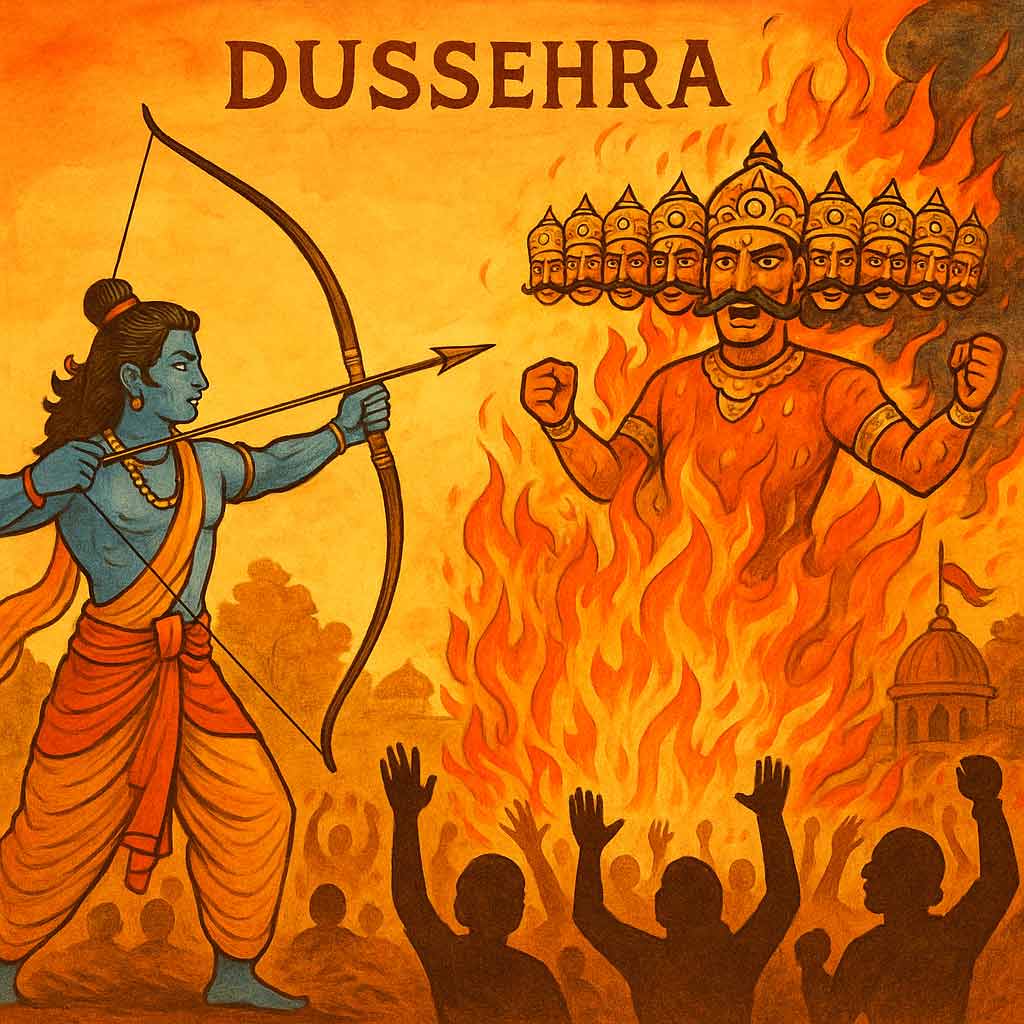

Dusserhra

Dussehra(September–October) The Triumph of Good over Evil Dussehra, also known as Vijayadashami, is one of the most significant Hindu festivals celebrated across India with great enthusiasm and spiritual fervour. It marks the victory of good over evil and righteousness over wickedness. Falling on the tenth day of the lunar month of Ashwin (September–October), it comes right after the nine days of Navratri and carries deep cultural, moral, and spiritual meanings. The word Dussehra is derived from two Sanskrit words — Dasha meaning “ten” and Hara meaning “defeat” — signifying the defeat of the ten-headed demon king Ravana by Lord Rama, as narrated in the epic Ramayana. The story of Dussehra varies slightly across regions, but the central theme remains the same — the triumph of virtue over vice. In northern India, Dussehra commemorates Lord Rama’s victory over Ravana, who had abducted his wife Sita. It is said that after a fierce battle lasting ten days, Rama killed Ravana and rescued Sita, symbolizing the triumph of truth and dharma. In many parts of the country, effigies of Ravana, his brother Kumbhakarna, and his son Meghnath are burned in open grounds to celebrate this victory. The burning effigies, accompanied by the thunderous sound of firecrackers, signify the destruction of arrogance, lust, and evil tendencies that reside within human beings. The festival teaches that even the mightiest power cannot stand against truth and righteousness. In the eastern and southern states of India, Dussehra coincides with the conclusion of Durga Puja, a grand celebration that honours Goddess Durga’s victory over the buffalo demon Mahishasura. According to Hindu mythology, Mahishasura was a powerful demon who had gained immense strength and created havoc in the heavens and on earth. The gods combined their energies to create Goddess Durga, who fought Mahishasura for nine days and nights and finally defeated him on the tenth day — celebrated as Vijayadashami, the day of victory. Thus, while northern India celebrates Dussehra as Rama’s victory, eastern and southern India celebrate it as the triumph of the Goddess over demonic forces. Both stories, however, convey the same eternal message — the ultimate triumph of good over evil. The festival also carries immense cultural and social significance. In many towns and villages, theatrical enactments of the Ramayana known as Ramlila are performed in open-air stages. These performances not only entertain but also serve as moral education, reminding people of the values of truth, honour, and sacrifice. The effigy-burning ceremonies bring together people from all walks of life, reinforcing a sense of community and shared celebration. In the south, devotees mark the day by beginning new ventures, buying new tools, books, or vehicles, as it is considered an auspicious time for new beginnings. The tradition of worshipping tools and instruments, known as Ayudha Puja, signifies respect for one’s profession and work. Beyond mythology and ritual, Dussehra also holds philosophical depth. It is a reminder that evil is not merely external — represented by Ravana or Mahishasura — but also resides within us in the form of ego, greed, anger, jealousy, and deceit. The burning of Ravana’s effigy symbolizes the burning of these inner vices. Every year, the festival encourages individuals to introspect and strive to conquer their personal demons. Dussehra’s universal appeal lies in its message of moral victory and renewal. It inspires courage, righteousness, and the confidence that truth will always prevail, no matter how powerful evil may appear. In a modern world often filled with conflict, inequality, and moral confusion, Dussehra serves as a timeless reminder that ethical living, compassion, and self-discipline form the foundation of a just and harmonious society. In essence, Dussehra is not just a festival; it is a celebration of human values — courage, truth, justice, and devotion. It teaches that no matter how many challenges or injustices one faces, righteousness and goodness will ultimately triumph. As the flames of Ravana’s effigy rise high into the night sky, they illuminate not only the end of evil but also the dawn of hope, virtue, and moral awakening — a lesson that remains as relevant today as it was thousands of years ago.

Deepavali

Diwali (October–November) The Festival of Lights, Joy, and New Beginnings Diwali, also known as Deepavali, is one of the most celebrated and cherished festivals in India, symbolizing the victory of light over darkness, good over evil, and knowledge over ignorance. The word Deepavali comes from the Sanskrit words deepa (lamp) and avali (row), meaning a “row of lights.” This radiant festival illuminates homes, streets, and hearts with its glow, spreading warmth, happiness, and hope. Falling in the Hindu month of Kartika (October or November), Diwali is celebrated with grandeur and devotion across India and by Indian communities worldwide. The festival typically spans five days, each carrying unique spiritual significance, and is observed by people of various faiths, including Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, and Buddhists, each interpreting it through their own cultural and religious lens. The origin and legends of Diwali are as diverse as India itself, with different regions celebrating the festival for different reasons. In northern India, Diwali marks the return of Lord Rama to Ayodhya after a 14-year exile and his victory over the demon king Ravana. To celebrate his return, the people of Ayodhya lit rows of oil lamps, symbolizing the triumph of righteousness and the dispelling of darkness. In southern India, the festival commemorates Lord Krishna’s victory over the demon Narakasura, representing the victory of divine truth over arrogance and evil. In western India, particularly Gujarat, Diwali also marks the start of a new financial year, when businesses close old accounts and open new ledgers, praying to Goddess Lakshmi for wealth and prosperity. For Jains, Diwali marks the day when Lord Mahavira attained nirvana, while Sikhs celebrate it as Bandi Chhor Divas, the day Guru Hargobind Ji was released from imprisonment. Despite these diverse stories, the core message of Diwali remains the same—renewal, hope, and the triumph of light. The preparations for Diwali begin weeks in advance. Homes and workplaces are thoroughly cleaned, painted, and decorated to welcome prosperity and positivity. People adorn their homes with colorful rangoli designs, diyas (oil lamps), and string lights, creating an enchanting sight after sunset. The fragrance of freshly prepared sweets like laddus, barfis, and halwas fills the air, while markets bustle with people shopping for new clothes, gifts, and festive delicacies. The lighting of diyas is not only a visual delight but also a spiritual act—signifying the removal of ignorance and the awakening of inner wisdom. Families come together to perform Lakshmi Puja on the main day of Diwali, offering prayers to Goddess Lakshmi, the deity of wealth and prosperity, and Lord Ganesha, the remover of obstacles, for peace and success in the year ahead. Diwali is also a time for sharing and giving, fostering social harmony and compassion. People visit friends and relatives to exchange sweets and gifts, reinforcing bonds of love and friendship. In many parts of India, fireworks light up the night sky, adding color and sparkle to the celebrations. However, in recent years, there has been a growing awareness about the environmental and health effects of excessive fireworks, leading to campaigns promoting a “Green Diwali.” Many communities now celebrate with eco-friendly diyas, natural decorations, and minimal noise, embracing the true spirit of the festival—joy without harm. Beyond its external beauty, Diwali carries a deep philosophical and spiritual message. The lighting of lamps signifies the illumination of the mind and soul, urging individuals to replace ignorance with wisdom, hatred with love, and despair with hope. It reminds people that darkness is temporary and can be overcome by perseverance and positivity. The festival also encourages introspection and gratitude—thanking the divine for blessings received and seeking strength to overcome life’s challenges. In this sense, Diwali is not just an external celebration but an inner awakening. In modern times, Diwali has become a global festival, celebrated in cities like London, New York, Singapore, and Sydney, where landmarks are lit up to honor the occasion. It brings together people of all backgrounds to celebrate unity, harmony, and cultural richness. The festival’s universal themes of renewal, hope, and light resonate across cultures and faiths, making it one of the most beloved celebrations in the world. Ultimately, Diwali is more than a festival—it is a way of life. It reminds us to nurture the light within ourselves, to spread kindness, and to overcome adversity with courage and faith. As the flickering lamps illuminate homes and hearts, Diwali inspires everyone to embrace new beginnings, celebrate togetherness, and keep the flame of goodness burning bright. Whether celebrated with grandeur in bustling cities or with simplicity in small villages, the spirit of Diwali unites millions in a shared message of joy, peace, and love—a reminder that light, in all its forms, will always conquer darkness.